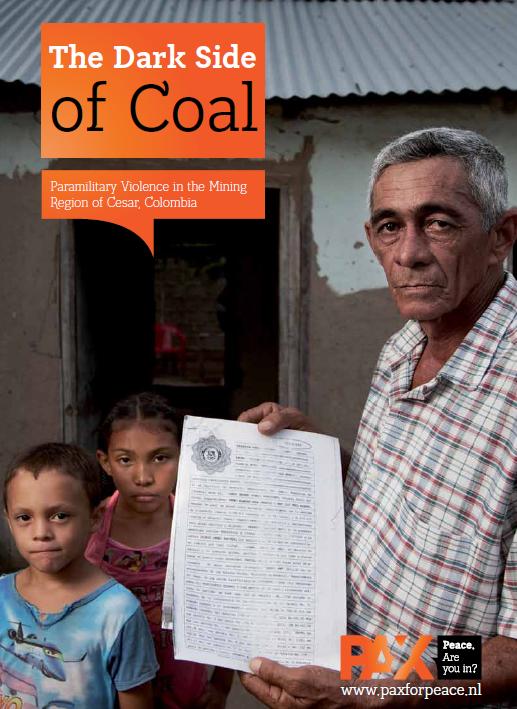

Fuente: PAX.

The Dark Side of Coal

Paramilitary Violence in the Mining Region of Cesar, Colombia

Contents

Introduction 8

Facts & Figures on Coalmining in Cesar 16

1. Violence in the Cesar Mining Region 22

2. Victims’ Voices Heard 32

3. Mining Industry in Wartime (1996–1998) 44

4. The Creation & Expansion of the Juan Andrés Álvarez Front (1999–2006) 52

5. Testimonies regarding the Funding of the AUC 56

6. Testimonies regarding the Exchange of Information & Coordination 64

7. Benefiting from Forced Displacement? 72

8. Europe & Colombian Coal 78

9. Responses from Drummond & Glencore 90

Executive Summary 102

Recommendations 106

Who is Who? 112

Annex A 118

Annex B 122

Endnotes 128

Executive Summary

This report is a study into the wave of paramilitary violence that swept the mining region of the northern Colombian Cesar department between 1996 and 2006, the effects of which reverberate throughout the region to this day. The report deals with the alleged role of the US-based coal mining company Drummond in this violence, and to a lesser extent that of Prodeco, a subsidiary of Switzerland-based Glencore. Both coalmining companies are selling a major portion of their production (roughly 70% in 2013) to European energy utilities such as E.ON, GDF Suez, EDF, Enel, RWE, Iberdrola, and Vattenfall.

The study was conducted at the explicit request of the victims of the violence and their family members; and with the report we hope to contribute to their endeavours to uncover the truth behind the violence and achieve effective remedy for the harm they have suffered.

Over the past three years, PAX has carried out numerous interviews with victims of human rights violations, former paramilitary commanders from the region, former employees of the mining companies and their contractors, human rights lawyers, and the Colombian authorities. A considerable part of the report, however, is constructed around court testimonies and depositions.

We have used the testimonies of seven ex-paramilitary commanders, three of Drummond’s former employees and contractors, and one Prodeco ex-employee. They made their statements under oath within the context of the Colombian Justice and Peace process, the ordinary Colombian justice system, and in the course of a recent US court case against the company under the Alien Tort Claims Act. Multiple sources allege that particularly Drummond, but also Prodeco, have been involved, in various ways, in human rights abuses during this period.

When Drummond and Prodeco started their coalmining activities in Colombia in the midnineteen nineties, Cesar was already a conflict-ridden region. The presence of the FARC and ELN guerrilla forces was affecting their operations. In 1996, a first group of paramilitary combatants of the AUC arrived in the region. In December 1999, a new AUC front – the Juan Andrés Álvarez Front – was created specifically with the aim of operating in the vicinity of the mining concessions and along the railway line. In the ensuing years, the Front grew to 600 members who spread fear and terror among the local population. On the basis of national police figures, we conservatively estimate that between 1996 and 2006 the Front and its predecessors in the region committed at least 2,600 selective killings, murdered an estimated 500 people in massacres, and made more than 240 people disappear. These figures also indicate that the paramilitary violence caused more than 59,000 forced displacements in the Cesar mining region.

In the early years of their operations, Drummond and Prodeco were well aware of the brutal methods used by the AUC to fight against the guerrillas and suspected guerrilla sympathizers.

The government registered human rights violations occurring in the region and, as was confirmed by former mining security officials, the security departments of the mining companies actively collected data on security incidents and the activities of illegal armed groups. Local army units moreover exchanged intelligence information with the companies on an on-going basis. We did not find any indication that the mining companies at the time urged the Colombian government to take steps to prevent the gross human rights violations in the region.

On the contrary, according to a former Prodeco military intelligence officer, the security departments of both companies played a crucial role in establishing the first contact between AUC paramilitary forces and company executives at an early stage in 1996. This contact allegedly led to the arrival of a first group of one hundred combatants to operate in the mining region. This was confirmed by an ex-paramilitary commander in the region who has claimed that the Juan Andrés Álvarez Front was created in 1999 upon the request of Drummond, specifically to defend the company’s mine and railway operations.

The report quotes nine sources alleging that between 1996 and 2006 Drummond provided substantial financial support to the AUC, in particular to the Juan Andrés Álvarez Front.

According to their testimonies, the methods of payment changed over the years, ranging from direct cash payments in the beginning, the channelling of funds through contractors, to the transfer of a fixed percentage of the mining companies’ revenue in later years. A former food services contractor for Drummond has testified under oath in different court proceedings that, at the request of Drummond, he channelled a total amount of USD 900,000 to the Juan Andrés Álvarez Front in monthly payments during the period late 1997–mid 2001. The payments were covered by a mark-up in his company’s invoices. Three ex-paramilitaries have testified that Prodeco also provided funding to the AUC in the region.

From the statements by former paramilitaries, a picture also emerges of frequent collaboration between the mining companies, the AUC, and elements of the army. Multiple sources have testified that Drummond and Prodeco passed on intelligence to local army units and the AUC.

According to four ex-paramilitaries, Drummond officials on several occasions discussed the general paramilitary strategy in the mining region with AUC commanders, for example to prioritize operations to focus on particular localities along the railway line. Three sources have testified that the private security company used by Drummond contacted the AUC directly if they saw a suspicious person and that the AUC organized killings on the basis of this telephone contact.

Three former paramilitary members and contractors have stated that in some instances the company directed the actions of the Juan Andrés Álvarez Front. They mention the case of the assassination of three Drummond trade union leaders in 2001 as a clear result of this coordination.

Several testimonies, by victims as well as by perpetrators, indicate that the mining companies have, in various ways, benefited from the human rights abuses committed by the AUC, and that they continue to do so to this day. Firstly, at least three cases of mass displacement took place on lands that nowadays are situated in or near the Drummond and Prodeco concessions.

Secondly, the assassination of mining trade union leaders and the continuous threats against their lives severely weakened the unions in the region and permitted the companies to refrain from improving the safety and working conditions of company employees. Lastly, the violence has silenced the critical voices of local communities and civil society organizations in matters of human rights and the social and environmental impacts of coalmining.

Both Drummond and Glencore firmly denied the sworn statements of the ex-paramilitaries, exemployees, and former contractors regarding their companies’ alleged support of the paramilitary AUC in the region. An extensive summary of the reaction of Drummond and Glencore to the testimonies can be found in Chapter 9.

The cycle of violence in the Cesar mining region has not yet ended. Today, the territory is plagued by criminal bands composed in large part of former members of paramilitary groups. Apart from their criminal activities, these illegal armed groups intimidate all those among the civilian population who demand truth, justice, reparation, and land restitution for victims of the paramilitary violence. In several of their written threats and public communications, these groups have declared that they are acting as the protectors of the interests of the mining companies in Cesar. However, as in the recent past, the companies keep silent about these disturbing developments and have failed to publicly distance themselves from the aforesaid statements.

PAX endorses the belief of the Cesar victims’ movement that the prevention of future human rights abuses in the Cesar mining region can only be achieved when the legacy of past injustices is satisfactorily resolved. It is time for Drummond and Prodeco to provide for, or cooperate in, legitimate processes to remediate the alleged human rights impacts of their mining operations.

This requires them, by themselves or in cooperation with other actors, to actively engage with the victims of the paramilitary violence in the mining region in an effort to remediate their scars from the past. Such engagement could contribute to uncovering the truth about an important episode of the Colombian conflict, and it may set an example for mining projects in other parts of the country.

Resumen Ejecutivo

Este informe es un estudio sobre la ola de violencia paramilitar que barrió al departamento del Cesar, en el norte de Colombia, entre 1996 y 2006, cuyos efectos resuenan hasta el día de hoy a través de la región. El informe trata el aparente rol en esta violencia de la empresa minera de carbón Drummond Ltd., con sede en Estados Unidos, y, en menor medida, de Prodeco, una empresa subsidiaria de Glencore Plc., con sede en Suiza. Ambas empresas mineras de carbón están vendiendo una gran parte de su producción (aproximadamente el 70% en 2013) a servicios de electricidad europeos, como E.ON, GDF Suez, EDF, Enel, RWE, Iberdrola y Vattenfall.

El estudio fue realizado por solicitud explícita de las víctimas de la violencia y sus familiares; y con el informe esperamos contribuir a sus esfuerzos para descubrir la verdad oculta detrás de la violencia y lograr un remedio efectivo para el daño que han sufrido.

Durante los últimos tres años, PAX ha realizado numerosas entrevistas con las víctimas de las violaciones de derechos humanos, con antiguos comandantes paramilitares de la región, con antiguos empleados de las empresas mineras y sus contratistas, con abogados especializados en derechos humanos y con las autoridades colombianas. Una parte considerable del informe, sin embargo, está construida alrededor de testimonios y declaraciones ante cortes judiciales. Hemos usado los testimonios de siete comandantes ex paramilitares, tres testimonios de antiguos empleados y contratistas de Drummond y un testimonio de un ex empleado de Prodeco. Estas personas rindieron sus declaraciones bajo juramento, dentro del contexto del proceso de Justicia y Paz en Colombia, del sistema de justicia ordinaria colombiano y en el transcurso de un caso reciente ante una corte estadounidense contra la empresa, bajo el Alien Tort Claims Act. Múltiples fuentes alegan que particularmente Drummond, pero también Prodeco, han estado involucradas, de varias maneras, en abusos de los derechos humanos durante este periodo.

Cuando Drummond y Prodeco iniciaron sus actividades mineras de carbón en Colombia, a mediados de los años 90, el Cesar ya era un departamento azotado de conflictos. La presencia de las fuerzas guerrilleras de las FARC y el ELN estaba afectando sus operaciones. En 1996, un primer grupo de combatientes paramilitares de las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) llegó a la región. En diciembre de 1999, un nuevo frente de las AUC – el Frente Juan Andrés Álvarez – fue creado específicamente con la intención de operar en la vecindad de las concesiones mineras y a todo lo largo de la vía férrea. En los años siguientes, este frente llegó a tener 600 miembros, quienes sembraron el temor y el terror entre la población local. Con base en las cifras de la policía nacional, hacemos un cálculo conservador de que entre 1996 y 2006 el Frente cometió al menos 2.600 asesinatos selectivos, asesinó a unas 500 personas en masacres e hizo desaparecer a más de 240 personas. Estas cifras también indican que la violencia paramilitar causó más de 55.000 desplazamientos forzados en la zona minera del Cesar.

Durante los años iníciales de sus operaciones, Drummond y Prodeco eran bien conscientes de los brutales métodos usados por las AUC para luchar contra las guerrillas y contra las personas sospechosas de simpatizar con la guerrilla. El gobierno registró las violaciones de los derechos humanos ocurridas en la región y, tal como lo confirmaron los antiguos empleados de seguridad de las empresas mineras, los departamentos de seguridad de estas empresas recolectaron activamente datos sobre los incidentes relativos a la seguridad y a las actividades de los grupos armados ilegales. Además, las unidades del ejército locales intercambiaron información de inteligencia con las empresas de manera permanente. No encontramos ninguna indicación de que las empresas mineras urgieran en esa época al gobierno colombiano para que tomara medidas tendientes a prevenirlas graves violaciones de los derechos humanos en la región.

Por el contrario, según un antiguo empleado de inteligencia militar de Prodeco, los departamentos de seguridad de ambas empresas jugaron un papel crucial en el establecimiento de los primeros contactos entre las fuerzas paramilitares y los ejecutivos de las empresas en 1996. Este contacto supuestamente llevó a la llegada del primer grupo de cien combatientes para operar en la zona minera. Esto fue confirmado por un comandante ex paramilitar en la región, quien ha alegado que el Frente Juan Andrés Álvarez fue creado en 1999 por pedido de Drummond, específicamente para defender las operaciones de la empresa en la mina y la vía férrea.

El informe cita nueve fuentes que alegan que entre 1996 y 2006 Drummond suministró un sustancial apoyo financiero a las AUC, particularmente al Frente Juan Andrés Álvarez. Según sus testimonios, los métodos de pago cambiaron con los años e incluyeron desde pagos directos en efectivo, hechos al comienzo, y la canalización de fondos a través de contratistas, hasta la transferencia de un porcentaje fijo de los ingresos de la empresa en los años posteriores. Un antiguo contratista de alimentación de Drummond ha testimoniado bajo juramento en diferentes procesos ante los tribunales, que él canalizó una suma total de 900.000 dólares para el Frente Juan Andrés Álvarez, en pagos mensuales, como lo solicitó Drummond, durante el periodo desde finales de 1997 a mediados de 2001. Los pagos fueron cubiertos con una anotación en sus facturas a la empresa. Tres ex paramilitares han testimoniado que Prodeco también suministró fondos para las AUC en la región.

De las declaraciones de los antiguos paramilitares también surge una imagen de frecuente colaboración entre las empresas mineras, las AUC y el ejército. Múltiples fuentes han testimoniado que Drummond y Prodeco pasaron datos de inteligencia a las unidades del ejército locales y a las AUC. Según cuatro ex paramilitares, empleados de Drummond discutieron en varias ocasiones la estrategia paramilitar general en la región minera con los comandantes de las AUC, por ejemplo para darle prioridad a operaciones enfocadas en sitios concretos a lo largo de la vía férrea. Tres fuentes han testimoniado que la empresa de seguridad privada usada por Drummond contactaba directamente a las AUC si veía a alguna persona sospechosa y que las AUC organizaron asesinatos con base en este contacto telefónico. Tres antiguos miembros paramilitares y contratistas han declarado que en algunas instancias la empresa dirigió las acciones del Frente Juan Andrés Álvarez. Mencionan el caso del asesinato de tres líderes sindicales de Drummond en 2001, como un resultado claro de esta coordinación.

Varios testimonios, tanto de las víctimas como de los autores, indican que las empresas mineras se han beneficiado de varias maneras de los abusos de los derechos humanos cometidos por las AUC y que lo continúan haciendo hasta el día de hoy. En primer lugar, al menos tres casos de desplazamiento forzado tuvieron lugar en tierras que actualmente están situadas en las concesiones de Drummond y Prodeco o cerca de ellas. En segundo lugar, el asesinato de los líderes sindicales mineros y las continuas amenazas contra las vidas de otros miembros han debilitado los sindicatos en la región y les permiten a las empresas abstenerse de mejorar la seguridad y las condiciones laborales de los empleados de las empresas. Y por último, la violencia ha silenciado las voces críticas de las comunidades locales y de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil en los temas de derechos humanos y los impactos sociales y ambientales de la minería del carbón.

El ciclo de violencia en la región minera del Cesar no ha terminado todavía. Actualmente, el territorio está plagado de bandas criminales compuestas en gran parte por antiguos integrantes de los grupos paramilitares. Aparte de sus actividades criminales, estos grupos armados ilegales intimidan a todos aquellos de la población civil que piden la verdad, la justicia, la reparación y la devolución de tierras para las víctimas de la violencia paramilitar. En algunas de sus amenazas escritas y comunicados públicos, estos grupos han declarado que ellos están actuando como protectores de los intereses de las empresas mineras en el Cesar. Sin embargo, como en el pasado reciente, las empresas guardan silencio acerca de estos inquietantes desarrollos y han fallado a la hora de distanciarse públicamente de las declaraciones ya mencionadas.

PAX avala la creencia del movimiento de las víctimas del Cesar de que la prevención de los futuros abusos de los derechos humanos en la región minera del Cesar solamente puede ser lograda cuando el legado de las injusticias pasadas haya sido resuelto satisfactoriamente. Ya es hora de que Drummond y Prodeco acepten su responsabilidad por los impactos en los derechos humanos de sus operaciones mineras. Esto requiere su compromiso activo con las víctimas de la violencia paramilitar en la región minera, en un esfuerzo por sanar sus cicatrices del pasado. Tal compromiso puede contribuir a hallar la verdad acerca de un episodio importante del conflicto colombiano y podría servir de ejemplo para los proyectos mineros en otras partes del país.